Everything You’ve Ever Wanted to Know about Bargue Drawings

If you’ve landed on this page or if you’ve been drawing for awhile, you’ve probably heard people talk about a mysterious exercise called Bargue drawing. Some folks think it’s the holy grail of drawing training, others think it’s a waste of time and plenty are still are wondering... who or what is Bargue??

Well, don’t worry, we’ve got answers for you! Let’s dive in!

What is a Bargue drawing?

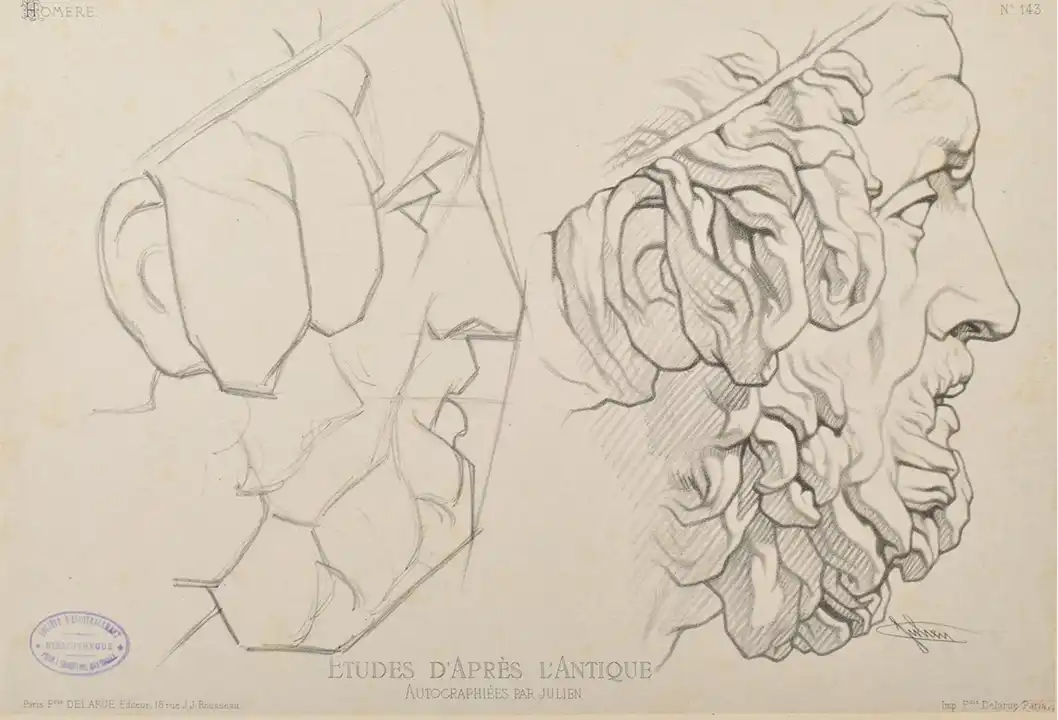

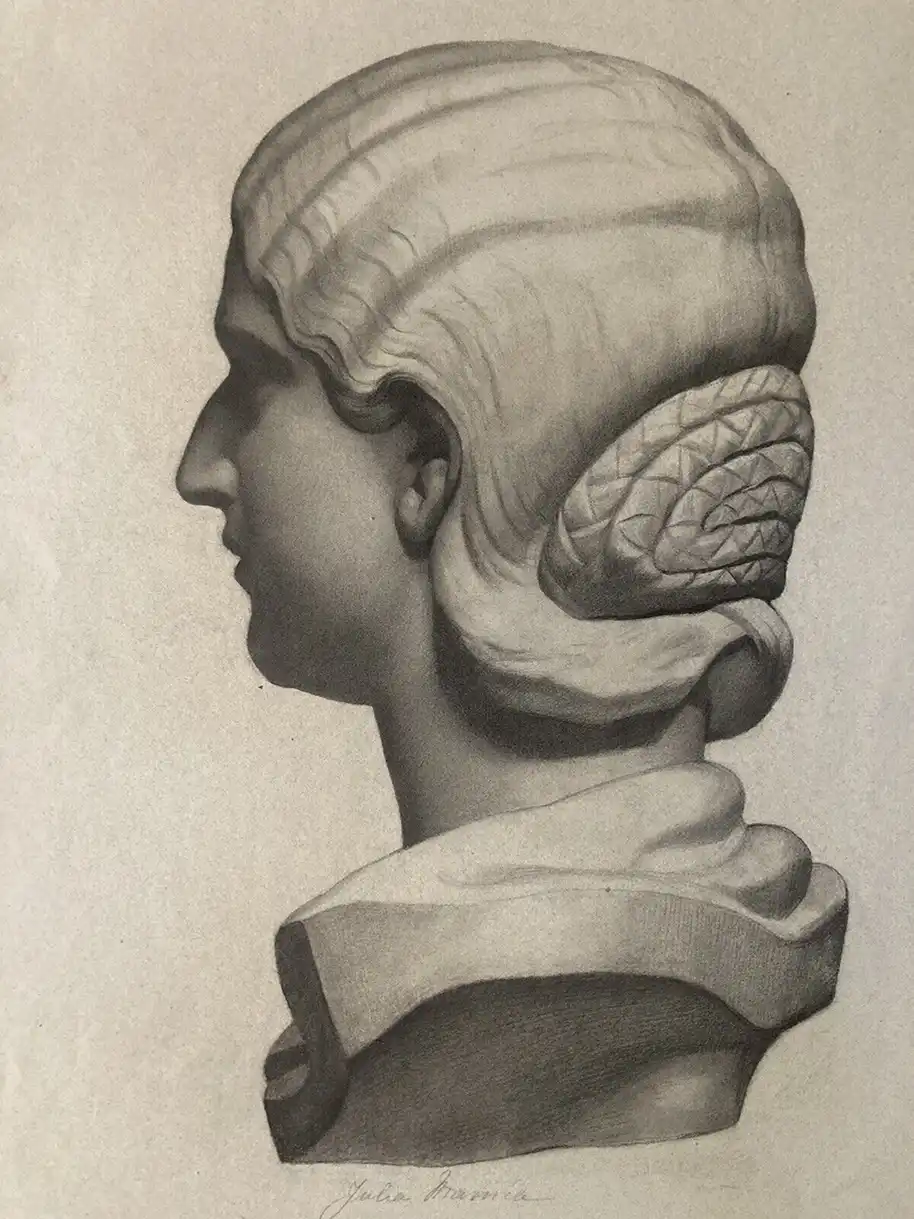

The Bargue course, officially the Cours de Dessin (Drawing Course), is a series 197 lithographic plates made by Charles Bargue between 1868 and 1871.

The first part of the course, and the most commonly used, is called Models after Casts (Modeles d’apres la bosse) and it was done with the counsel of the painter Jean-Leon Gérôme. Gérôme was a professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and likely provided example drawings from his students- the typical kind of academic work drawn from plaster casts. Bargue took these drawings and copied them on a lithographic stone, so they could be printed and sold.

The plates are meant to be used as “models” for students to copy, thereby gaining practical skills, but also educating their taste to look for simplicity and refinement. The drawings in the course go from simple schematics, to progressively complex figures.

This exercise, copying drawings or prints (lithographs, engravings), is called drawing from the flat, and it’s been an elementary exercise in many art studios for centuries. In fact, there were many drawing courses circulating in the 19th century, but because of Bargue’s clear diagrams and beautiful draftsmanship, his course was extremely popular and overshadowed most others.

These days, many art academies and ateliers (studios) consider the Bargue course to be an essential part of elementary art training. Students learn to make painstaking, mechanically exact copies of the plates, using an extravagantly sharpened, needle-like charcoal or graphite pencil point. The originals are copied line by line, hatchmark by hatchmark, and finished down to the minute details of filling in the grain of the paper to get perfectly even tones, without any blending or smudging allowed.

This process costs students weeks, sometimes months and frequently hundreds of hours for a single Bargue copy- it’s a tedious, mind-numbing form of busywork, but students work through it with a smile, thinking that this is the only way to learn, that the pain and toil is productive. And this is often reinforced by teachers, who take a misguided pride in how hard their students work, how willing they are to sacrifice their time and energy at the altar of “excellence”.

Of course, a certain amount of rigor, discipline and time is needed to learn new things, and the resulting drawings are often very accurate copies of the originals, but is this really necessary to draw well? Is this what Charlie Bargue would’ve wanted for us? Does learning to draw mean we have to suffer and even learn to dread drawing?

Well, simply put, no, no and NO.

How were Bargue drawings meant to be studied?

In fact, by the middle of the 19th century, drawing from the flat was not considered necessary at all- students at all serious Parisian ateliers, both in and out of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, started drawing directly from plaster casts. Copying plates like the ones in the Bargue course was mostly practiced by students in schools for industrial and decorative arts, smaller regional art academies, in foreign schools outside of France and by children and amateurs.

When the academic painter Tony Robert Fleury asked a student about her prior training and she said she had copied engravings as a child, he dismissed it and said “that’s nothing at all”- indicating that he didn’t consider drawing from the flat to be serious training. For him and most of his colleagues, only working from the cast and the live model counted as a real artistic education.

And even when people did Bargue drawings in the past, they didn’t use graphite or a needle-sharp charcoal point. Graphite was not a popular instrument used for serious academic studies- it was reserved for smaller sketches with a limited value range. Likewise, making a fully-shaded drawing using only the charcoal point is far too slow and tedious.

Edmond-Eugène Valton, a painter trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, had this to say in his book Le Dessin Pratique Pour Tous (Practical Drawing for All):

"For a somewhat large drawing, the graphite pencil in turn would be worth nothing, it would be too thin. It will be necessary to use either charcoal, the Conté pencil no. 2, or both combined. The stump is also good for spreading large, uniform tones, the thumb as well, being careful not to rub too much for fear of greasing the paper." (Source)

Similarly, in his 1868 book about the history of drawing instruction, the artist Louis-Joseph Van Péteghem writes:

"As for the shaded part of the Bargue and Gérôme models, they have too harsh a chiaroscuro, because the gradation of halftones is neglected; there are drawings where half of a figure is black and the other white; likewise, the shades are made to be copied with the stump and not with the crayon; hence a certain softness that is found in some of these models; but this flaw is easily corrected in practice, and we gladly forgive it in favor of the sketching and linework they advocate and so powerfully help to popularize." (Source)

Finally, Gérôme supervised the development of the initial parts of the Bargue course and his students drew in charcoal and crayon, shading with the stump- so again, this wasn’t some special technique unique to his studio, this was just standard practice for all academic art students in 19th c France. With this context, there’s no reason to believe the Bargue drawings would be done any differently.

Want even more proof??

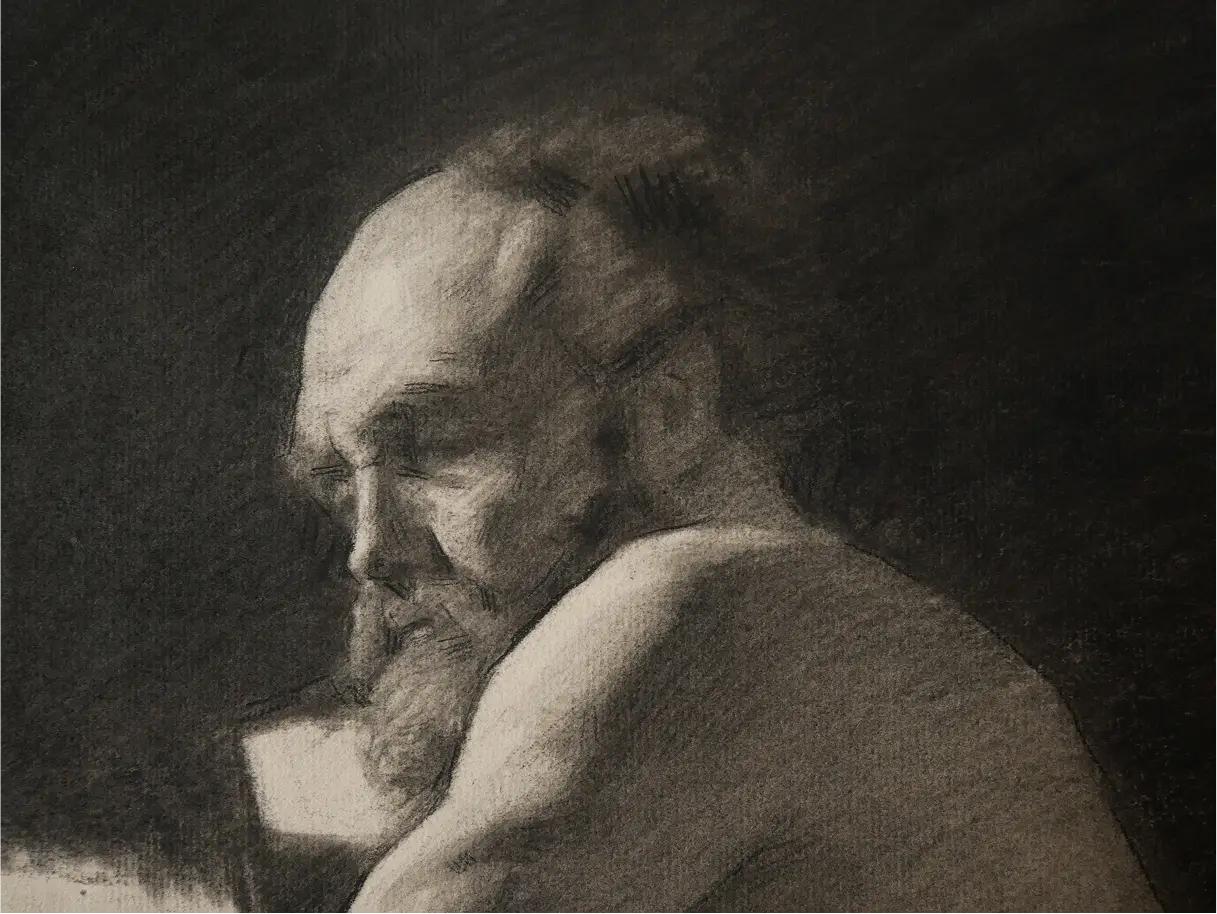

Is this all speculation? Do we have concrete examples of Bargue drawings done this way?? Actually, YES WE DO!! A number of original Bargue studies have emerged on ebay, done by French students from various schools, around the 1870s and 1880s.

So what do the drawings show us? Well, these are clearly meant to be serious copies- some even won prizes! Even so, their concern is with a broad general accuracy- matching the overall angles, structure and values of the forms, without delving into obsessive detail. And on closer inspection, these drawings show clear signs of the soft, smoky smudging produced by the stump, with only minimal lines used for accents- none of the hard, grainy texture produced by working only with the point.

We even have unfinished drawings that clearly follow a 2-stage process- a lighter sketch in charcoal, followed by a more elaborate shading in full value, likely using a Conte crayon or Conte powder (called sauce or crayon sauce). In fact, of the 3 example drawings below, 2 are obviously smudged and stumped- only the more rudimentary drawing on the far left seems to have been done without stumping.

Is the real process a long-lost secret?

Not at all! Bargue drawings are still a great way to learn about basic accuracy, simplification and form, along with the use of your materials. And it’s entirely possible do to them the way they were intended and derive all the benefits from them, without taking hundreds of soul-crushing hours to do so.

The first 3 drawings are Bargue copies done a few years ago by Patrick Süss, one of my former students- they’re around 16x12 inches and took 4-7 hours to complete, using charcoal, Conte crayon and the stump. Likewise, Halftone Studio’s very own Jake Taplin did this 18x24 inch copy in about 10 hours, using the same materials.

Bargue copies by Patrick Süss

If you think about it, full academic figures from life and from the cast took 12 hours to do- why would a drawing from the flat take any longer? And by keeping the time limits within this range, you get a chance to take your time and really learn from the plates, while still being able to produce a several of them in a month, giving you the balance between in-depth study and mileage that is necessary to make progress in any discipline.

So how do I draw Bargue plates?

While Bargue didn’t leave any instructions about how to approach the plates (they were sold more like trading cards rather than as a book), we do have some great options if you want to get started, and they’re FREE!

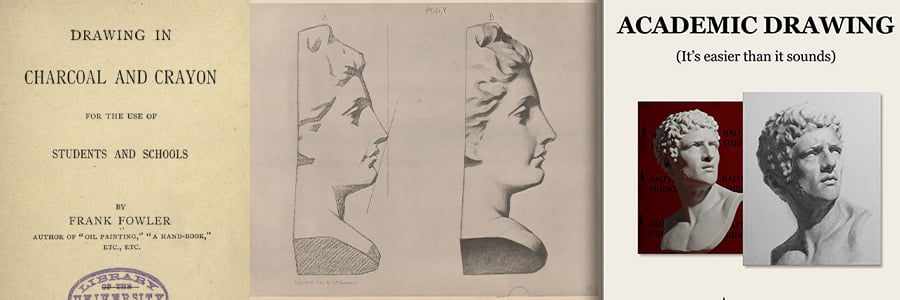

Frank Fowler, a friend of John Singer Sargent’s and a fellow student of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, wrote a book called Drawings in Charcoal and Crayon in 1885, which was intended “for the use of students and schools”. The book is short and includes all sorts of information about academic drawing, from paper and stumps, to charcoal and Conte crayons, and basic exercises. The book also came with a set of large plates, which were not lithographs, but actual photo reproductions of Fowler’s original drawings (heliotype process).

Copies of the book are not hard to find, but it’s only the text- the plates are always missing. However, after much research, I was able to track down the only known copy of the Fowler plates a few years ago, and now, we at Halftone Studio are happy to offer you access to these exclusive scans for FREE!

The drawings are very similar to the ones in Bargue course, but because they’re not lithographic copies, they show the grain of the paper and the slight sketchiness of actual academic drawings. Most importantly, Fowler includes actual instructions for copying the plates and the process involves... you guessed it- working with charcoal, Conte crayon and a stump!

Now, if you want to ease into things with step-by-step instructions in plain, modern English, you can also check out our FREE 13-page pdf academic drawing guide! Jake goes through and explains the same concepts as the Fowler book, with a wealth of pictures, explanations and everything you need to get started now!

You can also view high resolution images of the Bargue plates here: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52517498w/#

Conclusion

So what do we make of all this? In the end, you can definitely learn a lot from copying Bargue plates, just don’t get stuck doing it for too long or spending too much time on each drawing.

The value of the exercise is not in the drawing itself, the value is in what you learn- the concepts and skills that you keep for a lifetime, long after this particular drawing is forgotten.

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

%201.webp)

%20Scan%20by%20Ramon%20Hurtado.webp)

%20Scan%20by%20Ramon%20Hurtado.webp)

%20Scan%20by%20Ramon%20Hurtado.webp)

%20Scan%20by%20Ramon%20Hurtado.webp)

%201%20copy.webp)